In spite of decades of extensive research and hundreds of billions $ spent, cancer remains poorly curable disease, one of the main reasons for human deaths with tendency to increase in its incidence due to development of diagnostics approaches and more rapid progress in curing other lethal diseases. The underlying reasons for this unfortunate situation are manifold. Cancer develops from our own cells and therefore by its nature closely resembles healthy cells making selective eradication of tumor cells a difficult task. Cancer is creative: it evolves, like living organisms, according to Darwin’s selection with rapid acquisition of altered variants gaining multiple aggressive properties, including resistance to treatments. Cancer phenotype results from a variety of combinations of genetic and epigenetic changes making each tumor a distinct unique case thereby complicating development of universal treatments. Finally, large proportion of genetic alterations acquired by cancer cells does not provide druggable molecular targets since they are associated with loss, rather than gain, of function (i.e., loss of tumor suppressor genes). The major trend in drug discovery and development in oncology relies on the use of rationally selected (based on personalized medicine diagnostics) drug combinations, thus reducing the risk of development of resistant variants. Another gain in cancer treatment efficacy is expected from discovery and exploration of more “universal” molecular targets, what would make development of resistant variants less probable. One of the prospective sources of such targets is the factors essential for viability of specific tissues.

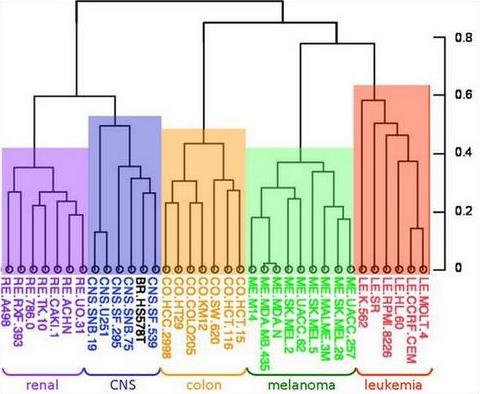

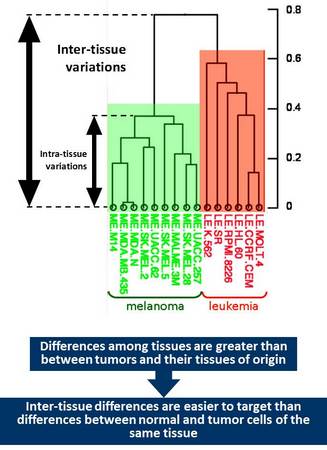

Even at most advanced metastatic stages of progression, tumors commonly retain properties of their tissue of origin. This phenomenon of tight connection to its “epigenetic destiny” is reflected by the possibility of recognition of tumor type by its morphological and molecular features and illustrated by dendrograms of gene expression patterns that consist of clusters of cancers originating from the same tissue that are clearly separated from each other.

The reality is that differences among cancers originating from common tissue are far less pronounced than among cancers of different origin. In other words, differences between cancer and its corresponding normal tissue is less pronounced that differences among tissues.

This consideration suggests that if there are factors that are essential for the viability of a particular tissue tumor cells originating from such tissue would likely retain dependence on such factors. Pharmacological targeting of such factors would likely result in selective tissue toxicity – regardless whether it consists of normal or transformed cells. Such tissue specific targets could be utilized for cancer treatment but only for those tissues that are either not essential for the viability of the whole organism or can be safely replaced. Tissues that belong to these categories include those associated with sexual function (breast, prostate, ovary, and cervix), melanocytes and hematopoietic system. The latter one is obviously essential for our viability but can be fully regenerated using stem cell therapy.

Importantly, there are several bright precedents of successful drugs that act via tissue specific mechanisms and that are actually not anticancer but rather antitissue drugs. They can be divided into three functional categories: (i) targeting signaling pathways essential for viability of cells of certain differentiation (e.g., anti-androgens and androgen receptor targeting molecules used for treatment of prostate cancer), (ii) targeting specific branches of cell metabolism that certain tissues uniquely depend on (e.g., bacterial asparaginase used for treatment acute leukemias since lymphocytes, as well as some leukemic cells, lack the ability of de novo synthesis of asparagine), (iii) directed against cell type-specific surface molecules (e.g., cytotoxic drugs based on CD20 targeting antibodies used for treatment leukemias that retain expression of this differentiation marker).

Therapies that are based on tissue targets are not necessarily equally toxic to normal and transformed cells. Thus, tamoxifen, an estrogen receptor antagonist, caused growth arrest in normal but frequently induces apoptosis in transformed breast epithelial cells.

Anti-tissue drugs are expected to have several advantages vis-à-vis other anticancer agents. For example, they are directed against intrinsic and nearly universal property of cancer cell – its basic epigenetic resemblance of normal cells of certain tissue. The fact that tumor cells almost never lose their “epigenetic destiny” suggests that it would be equally difficult for them to acquire resistance to anti-tissue drugs. High tissue selectivity of this type of drugs to the cells of specific differentiation restricts their general toxicity, which is a common problem for many conventional anticancer drugs. All these ideas stimulated OncoTartis to focus its R&D program on development of anti-tissue drugs.